[Warning: contains a brief mention of sexual violence and major spoilers for Alien³ ]

Welcome to an occasional series of posts where I kick around sequels that are widely derided and make a case for their re-evaluation.

– Bangs gavel –

So, in the dock before us today we have: Alien³.

The case against the second sequel to Squidly Rott’s (sorry) haunted house in space film is pretty well documented, but let me summarise it here.

- In its first ten minutes, the movie does away with two of the emotional anchors of its immediate predecessor, Aliens, namely Newt and Hicks. Emotionally it’s all downhill from here.

- There are long stretches of the movie where there’s not much tension (and very little else).

- The quadrupedal alien, aka man’s worst friend/xeno-woof, is objectively goofy.

- The inhabitants of Fiorina 161 (Fury) present a cast of poorly developed characters, most of whom all blur into one dude with a skinhead and a Bible-itch.

- They kill Ripley

- THEY KILL RIPLEY

- I SAID THEY KILL RIPLEY!

Traditionally, the movie’s apologists have pointed to the chaos around the film’s production and it’s worth taking a moment to remember exactly how much of a definition of development hell this movie was.

So stay frosty, people, I’m going to do this as quickly as I can, (you can also just skip ahead. For those gentle readers with a yen for this sort of grimoire there’s an in-depth account here):

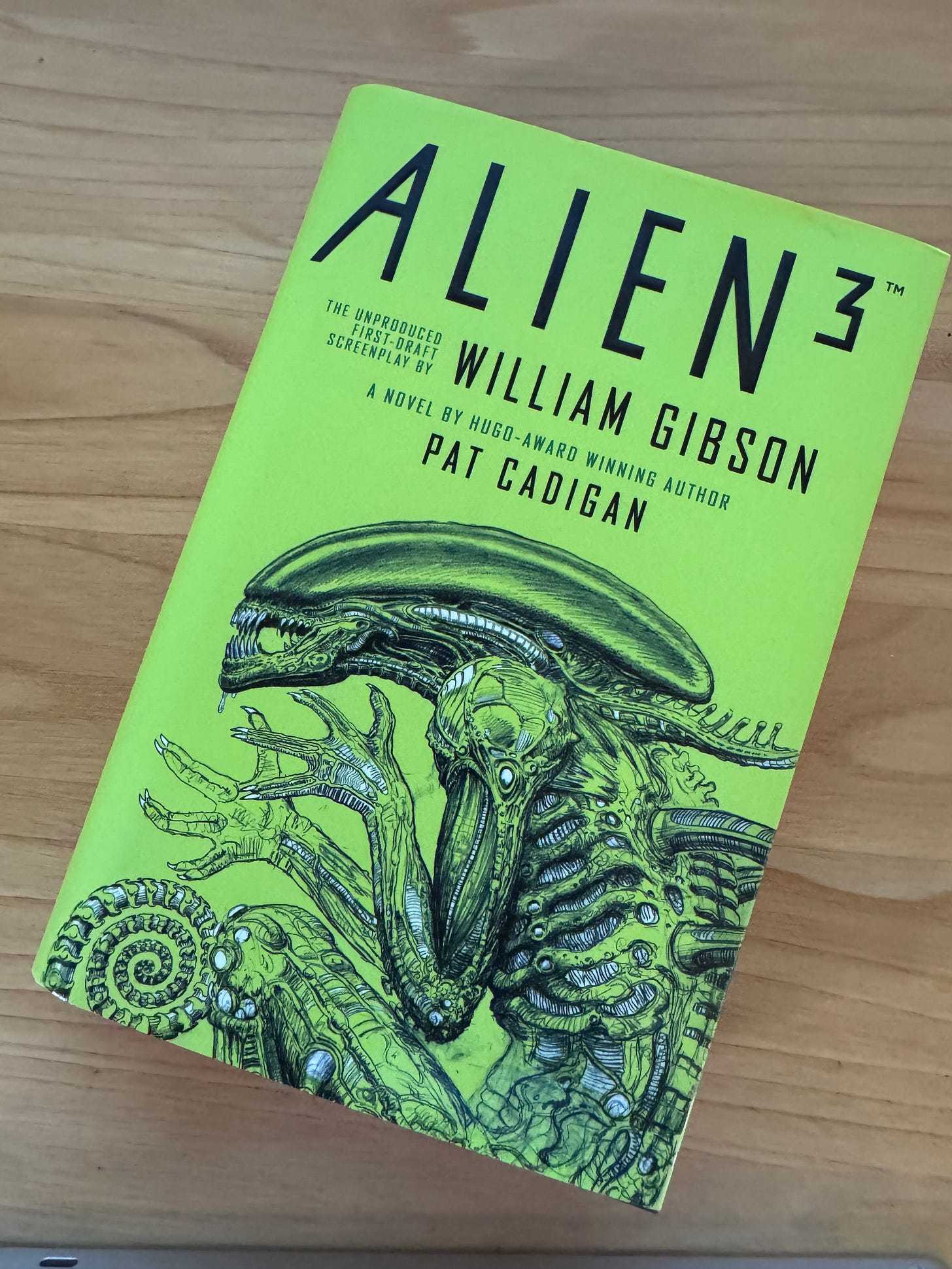

Producers Walter Hill & David Giler hired William Gibson for a cyber-punk styled sequel that Fox airlocked, then Renny Harlin (Die Hard 2) came aboard with Eric Red (Near Dark) just as Sigourney Weaver became disillusioned on the series’ obsession with guns, so David Twohy (Critters 2) delivered a Cold War-in-space draft without Ripley until Fox demanded her reinstatement, after which Vincent Ward (The Navigator) pitched his space-monks on a five-mile wooden planet with writer John Fasano before being jettisoned because, well, actually insane, whereupon rookie David Fincher inherited the mess with Larry Ferguson (Highlander), whose portrayal of Ripley Sigourney Weaver rejected, which forced Hill & Giler back, only for them to be secretly rewritten by Rex Pickett when Fox hated their ending, in a move worthy of Weyland-Yutani itself. Giler then produced another nine(!) revisions of the movie, but by this point they were already building sets.

(Phew.)

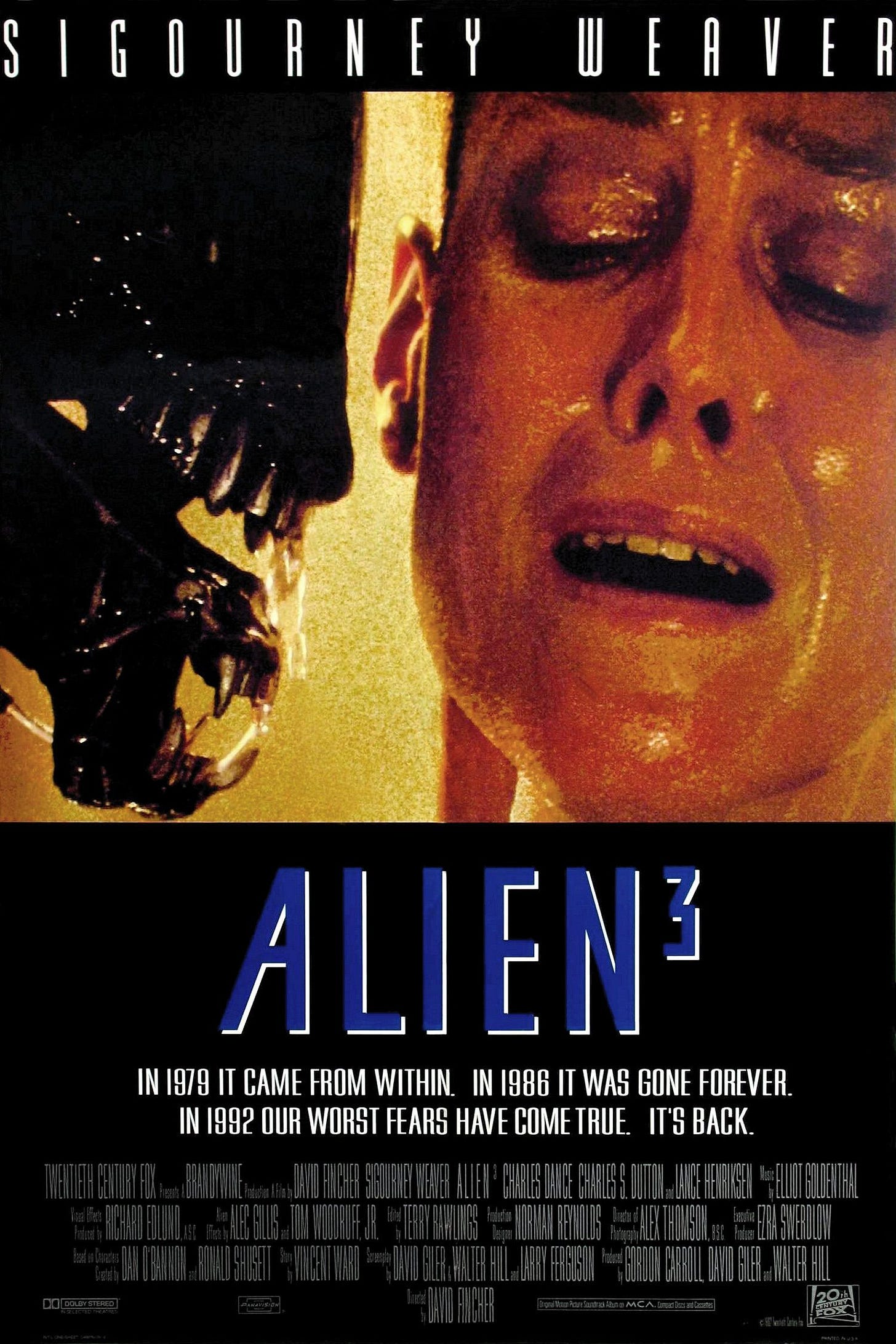

David Fincher has famously stated that working on Alien³ was the worst experience of his life due to Fox’s overbearing presence. After filming wrapped, there were extensive reshoots and extra sequences inserted into the film at the studio’s insistence prior to its release. (And let’s not even mention those dire publicity photos of poor old Sigourney in a bald cap).

Eventually, the movie was released in 1992 to very mixed reviews and domestic underperformance. Fincher himself (perhaps unsurprisingly) treats the film the way the rest of us treat the last two Indiana Jones sequels. I mean, there were only ever three Indy movies right?

But, despite (and perhaps because) of this, Alien³ is deeply weird and eerie, certainly possessed of a more haunted and tragic atmosphere than any predecessor or sequel. Certainly, I can’t imagine any contemporary franchise instalment taking the risks this film does and one could make the case that the film’s balls-out nutso bravery flies in the face of the reheated duds that have come in its wake.

So, working through the common objections one by one:

Newt & Hicks, nixed.

Yeah, a difficult one, but I think Newt and Hicks not making it to Fury works pretty well as a statement of intent. This film is a departure from what has come before and it sets the tone unashamedly for what’s to come. This isn’t going to be a gung-ho film about space marines.

Newt and Hicks’ deaths also mean that Ripley is grieving throughout the narrative and Weaver’s performance is easily the best thing about the film. In fact, I’d argue that it’s her best work in the series. The loneliness, vulnerability and strength that she brings to the portrayal of grief here are visceral.

Nothing to see here, (prison) guvnor

Similarly, I’d argue that the long lingering shots of the corridors and ventilation shafts that comprise Fury’s prison facility are freighted with a deep sense of liminal horror. The opening scene, where the camera creeps through the crash debris of the EEV, its slow tracking through the tunnels and shafts of the lead-works combined with the surveillance footage of deserted corridors, crackling fluorescent lights and humming machinery are all reminiscent of Nikolaus Geyrhalter’s deep-time classic Homo Sapiens. These are all spaces that should be populated, but aren’t, possessed of a sense of dread, of something missing or withheld, charged with the same creepypasta unease as the Backrooms.

if you’re enjoying this, you could buy me a cup of tea

Depopulated, de-centred

Nowhere is this eerie payload more evident than in the emergence of the creature itself. This chest-bursting moment is at complete odds with the gross-out splatter-core of the original movie. In both the theatrical version and the assembly cut the alien’s birth is intercut with Hicks and Newt’s funeral, but in each version, the xeno-woof (theatrical)/oxo-morph (assembly cut) emerges from its animal host in an unpeopled space. In the assembly cut ,the birth is even followed by a long, lonely pull-out from Babe the ox showing the birth site surrounded by empty space.

Even with poor Spike the dog’s death throes in the theatrical cut, the birth scene has an odd, disassociated feel to it more than one of straightforward horror. Partly, I think, this is because at this point in the series chest-bursting had become an expected staple of the Alien movies, but also because, yet again, this pivotal scene is happening unbeknownst to Ripley and the prison population. The humans are de-centred in their own story.

Xeno-woof/Oxo-morph

Much has been made of Fincher’s dog-in-a-suit xeno-woof, but in the film’s defence the only dog shots are mercifully brief and, in the assembly cut, were cleaned up by the DVD restoration team with greatly improved compositing. For me, the creature works as a classic form of weird ontology that upsets categories, is it a dog/ox/alien? The cute post-birth puppetry of the bambi-burster only reinforces how disturbing the creature’s mutability is.

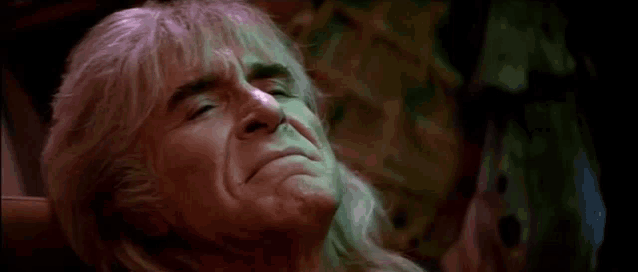

Look at me! I am soooo cute!

But also, I will eat your fucking face.

A seven foot walking cock with metal teeth

It’s no secret that H.R. Giger designed the xenomorph to be a seven-foot ambulatory cock with metal teeth, but Alien³ is the only movie in the series that draws an explicit parallel between the creature’s threat to bodily autonomy and sexual violence.

From this point of view, it’s possible to view the prisoners’ lack of individuality, specifically their shaved heads, uniforms and blurred identities as a way of collapsing them into a kind of faceless hostile masculinity.

Certainly, from her first entrance into the prison mess hall, Ripley is the focus of a predatory male gaze and her female identity is blamed explicitly by the prisoner’s leader, Dillon, for bringing “temptation” into their midst.

This ugly mood comes to a head most starkly when a group of prisoners attempt to sexually assault Ripley at the lead-works, but is also directly paralleled in the way in which the alien itself “leers” over her later when it traps her in the infirmary, its secondary jaw hovering with what seems to be sexual menace.

Both of these grim moments stage Ripley’s body as a site of threatened violation, reinforcing patriarchal stereotypes and drawing uncomfortable parallels between male and monstrous aggression.

Chip in, so I can buy a bald cap of my very own?

THEY KILL RIPLEY!

Yes, they do. But there’s a grace and beauty in her final sacrifice. It can be read as a final and definitive act of agency and autonomy. A noble fuck you to Bishop 2 and the Weyland-Yutani goons trying to exploit her and the alien embryo that she carries.

Again though, the film (at least in its theatrical version) delivers a strange and disturbing final image. In her last moments, as Ripley tumbles to her death, the alien bursts from her chest. She grabs it, holding it in an uncanny mirror of a mother-infant embrace, cradling it until they’re both swallowed by the molten metal below.

It’s a touching and deeply weird moment, which feels to me at least, like a fitting and dignified capstone to the trilogy.

In the end, Alien³ may be flawed, but I would say that its utter strangeness and sombre mood make it far more than a failure. Yes, it is bleak, but it’s also a very weird and eerily singular film with an emotional impact that, for me at least, lingers long after the credits have rolled.

But, more importantly, what do you think?

Playlist:

- Previous issue exploring the Backrooms and how they relate to the concept of the digital eerie.

- Fascinating article by Ghost Horses Writing Page on the Backrooms and the liminal.

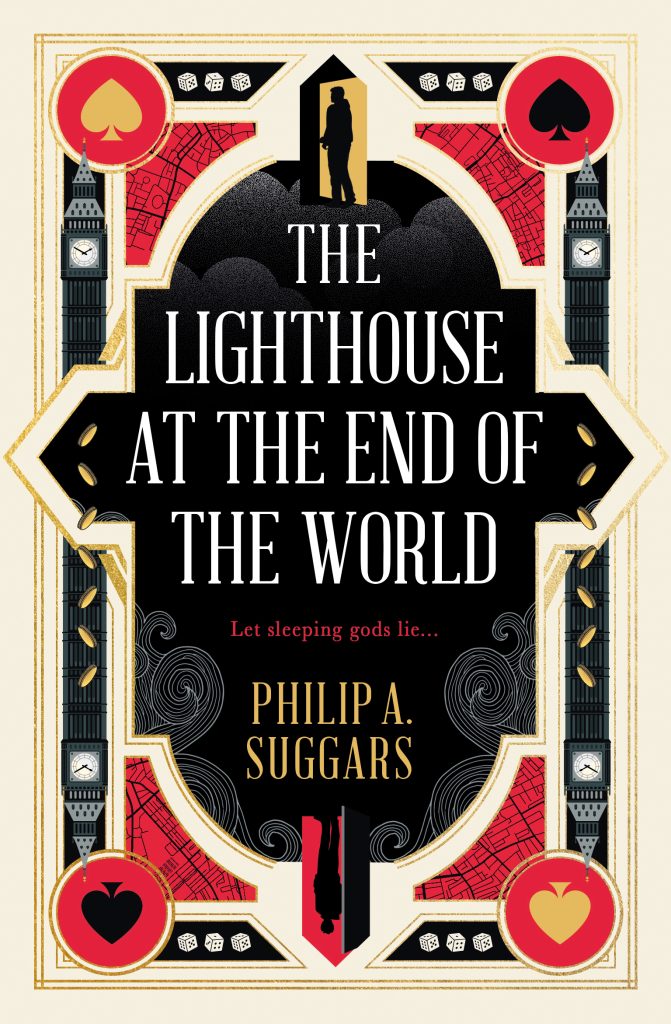

My debut fantasy novel, The Lighthouse at the End of the World is published on April 7th 2026 by Titan Books. Pre-order it here.